A Nation of Innovators

The story of how the federal government became an innovation evangelist in the 1960s is an account of fits, starts, and ideological ambiguity.

In 1967, as protests spread across the nation, a cadre of technologists who had infiltrated the federal government released a manifesto. Amid polarization and upheaval, these self-styled innovation experts proposed an optimistic future with missionary zeal. “Invention and innovation,” they declared, “lie at the heart of the process by which America has grown and renewed itself.”

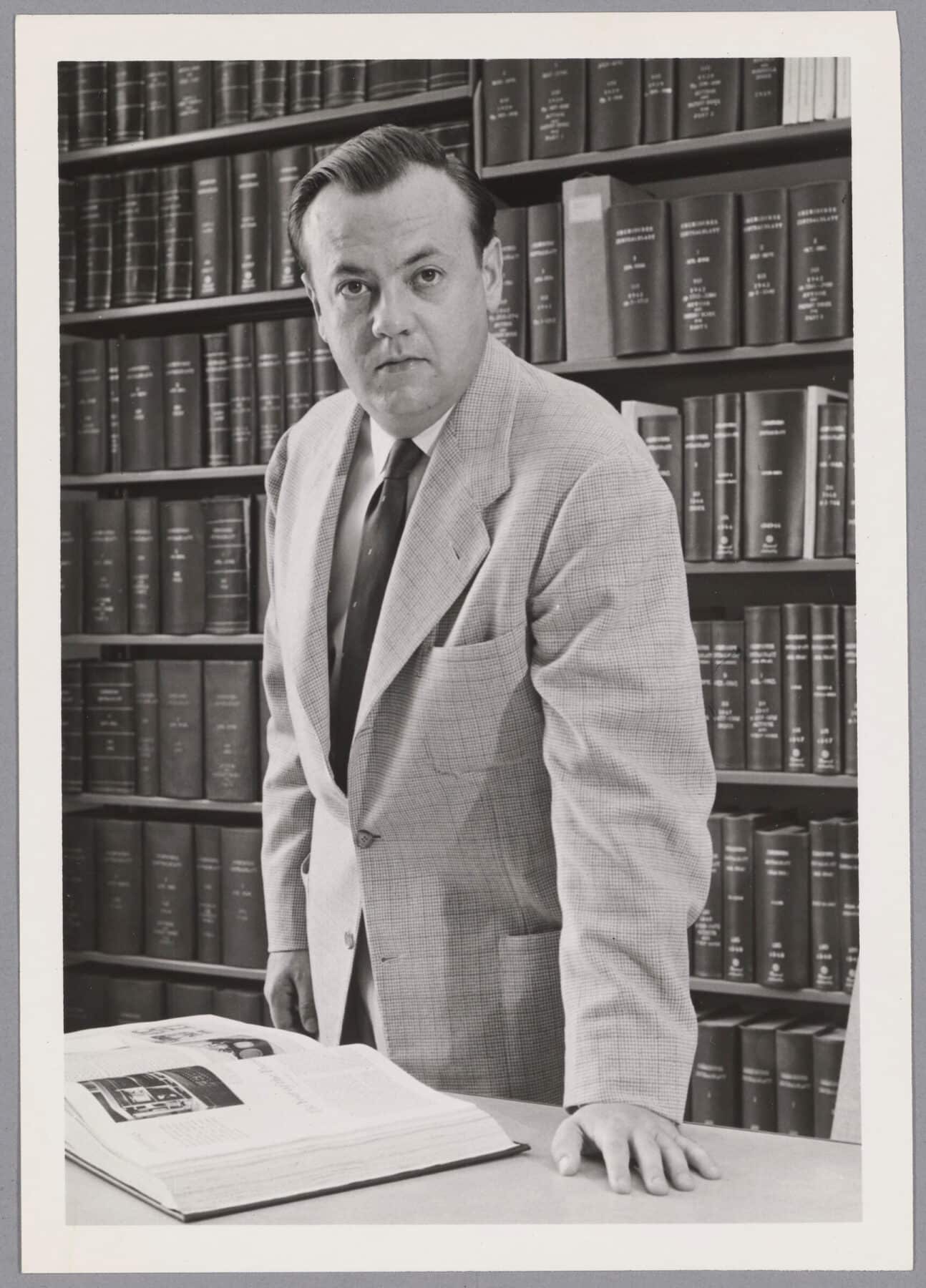

The federal government hired the ringleader of these bureaucratic innovators during the Kennedy administration. In 1962, J. Herbert Hollomon, General Electric’s top research director, joined the Department of Commerce as first assistant secretary for science and technology. Unlike the Cold War physicists who advised the government on super weapons from their positions in universities and national laboratories, Hollomon was an industry man. The 42-year-old metallurgist had earned his bachelor’s and doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology while serving the war effort at the Watertown Arsenal. He then spent sixteen years rising through General Electric’s ranks. He was a visionary, a recruiter of talented misfits, a prolific writer, and a polarizing reformer.

The Department of Commerce does not feature prominently in histories of postwar science and technology. Yet since its founding in 1903, Commerce had always performed important technological functions that included the National Bureau of Standards, the Weather Service, and the Patent Office. Hollomon’s appointment was a concerted effort to remake the department as a space-age home for civilian technology. He envisioned the agency as a nimble, research-based clearinghouse and coordinator that would act as an accelerator of American industry.

Commerce’s innovation initiatives were building blocks of what the Johnson administration came to call “creative federalism.” They took an interdisciplinary and total approach that linked the federal government to states, municipalities, and private industry, a model employed in President Johnson’s Great Society programs such as Head Start and Model Cities. However, the most lasting work of Hollomon’s innovation offices was conceptual. He and his staff generated new knowledge about the innovation process to “establish a national climate that nurtures and cultivates technological creativity.”

More than any other individual, Hollomon helped to integrate “innovation” into the government lexicon. He described innovation as the “key to a vibrant, competitive domestic economy and the best bet for the prevalence of American enterprise in the markets of the world.” He argued that the massive flow of resources into research and development had not produced effective results for everyday Americans because more than two-thirds of the billions of dollars spent on R&D went to space, defense, and atomic energy.

Hollomon saw the nascent idea of innovation as a solution to poverty and infrastructure modernization. After Kennedy’s assassination, he integrated innovation initiatives into Johnson’s Great Society, working with a coalition of liberal and centrist congressmen to pass legislation enabling his signature initiative, the State Technical Services (STS). STS brokered public-private partnerships across all fifty states based on the nineteenth-century land-grant model. Projects supported by STS included short courses in engineering management, information services on sewage waste treatment, and matchmaking between small businesses and university experts. President Johnson declared that the bill would “do for American businessmen what the great Agricultural Extension Service has done for the American farmer.” In the process, the act would “prevent more Appalachias,” in which entire regions of the country were left behind in an innovation age.

Hollomon also applied his vision of innovation to the government itself. He created internal programs such as the Science and Technology Fellowship to build a cadre of scientific experts who knew their economic ABCs. Johnson’s aide Joseph Califano Jr. described the program as part of a larger fusion of “the politics of innovation and the revolution in government management it has inspired.”

This is the story of how experts inside the federal bureaucracy initiated a decisive shift in beliefs about and policies toward innovation—a story highlighting ideals that came to be overshadowed by government disfunction and the emergence of Silicon Valley as a center of American power.

Invasion and “unreasonable men”

Hollomon and his team drafted an enduring blueprint for American innovation. Emphasizing the insurgent nature of innovation, the human qualities of innovators, and the appropriate policy environment to harness both for national progress, the Department of Commerce’s vision of an innovation nation came together in a 1967 report that it distributed to every US congressperson and state governor. The document, Technological Innovation: Its Environment and Management, came to be known as the “Charpie Report” after its chairman, Robert A. Charpie, then president of chemical company Union Carbide. However, it was largely conceived and written by a Hollomon protégé, Daniel DeSimone, a former Bell Laboratories patent lawyer.

The Charpie Report asked what the federal government could do to enhance innovative activity in the United States. It started with a broad definition of innovation as “the totality of processes by which new ideas are conceived, nurtured, developed and finally introduced.” Fostering innovation required understanding a complex ecosystem, and the government’s role within it. Innovation was a regional phenomenon. Its main ingredients included universities, venture capital, entrepreneurs, and lines of communication between them. But the essential unit for investigating innovation was not the university or government laboratory; it was the private company—particularly small businesses. The committee’s heroes were small start-up firms created by entrepreneurs, which suffered the most from policies created to regulate large corporations.

Hollomon argued that the massive flow of resources into research and development had not produced effective results for everyday Americans because more than two-thirds of the billions of dollars spent on R&D went to space, defense, and atomic energy.

Innovators were at the core of the nation’s innovation system. In congressional testimony on the patent system, DeSimone expounded on the contributions of these “unreasonable men”: They were technically knowledgeable, cosmopolitan, risk-taking individualists who would stop at nothing to see their ideas succeed. Expanding on DeSimone’s examples of unreasonable men, the Charpie Report showcased the work of independent inventors and small organizations behind dozens of technologies: air conditioning, for example, and the zipper. And it explored the common challenges these innovators faced, such as lack of capital, lack of business training, and a surplus of risk-averse naysayers.

The Charpie Report’s core message was to call out a general “abundance of ignorance” about the nature of innovation. The committee lamented a lack of existing research, which it used to justify basing its conclusions on personal experience. The group argued that harnessing innovation for national progress did not require substantial policy changes; however, it demanded a change in “attitude and environment.” Innovation was a “foreign language” with rules, uses, and learned habits. The government therefore had an important role as the nation’s literacy teacher.

Toward a national innovation system

Revolt, rather than renewal, was the prevailing national mood when Hollomon’s team at Commerce released the Charpie Report. Its architects worked on the optimistic side of a widening societal chasm. Across issues as disparate as the Vietnam War, environmental pollution, and civil rights, many commentators had come to identify science and technology as root causes of the nation’s unrest. At the same time, a surging conservative tide, culminating with the election of Richard Nixon, eroded over a decade of liberal initiatives.

Hollomon was a casualty of these shifting fortunes. In the waning days of the Johnson administration, he departed for a new position as president of the University of Oklahoma. Hollomon’s departure stood as a warning to future reformers of the perils of being perceived as a bureaucratic innovator.

Innovation initiatives, however, did not get thrown out with the liberal bathwater. On the contrary, by 1972 the Nixon administration made innovation a major priority. Why? For one, DeSimone stayed in the new administration and he and other career bureaucrats took on greater responsibilities under Nixon. Likewise, many of the industrial scientists, patent lawyers, and entrepreneurs Hollomon had tapped as advisors continued to serve. Even as Nixon’s staff reinterpreted how technology ought to be applied to civilian needs, they extended Hollomon’s ideas into new federal agencies.

During Nixon’s first term, science and technology policy nonetheless was marked by uncertainty and instability. The scientific community viewed Nixon’s victory as the end of a golden age. For over a decade, scientists had received billions of dollars under the premise that basic science would generate tangible social benefits. In the process, scientists found themselves in the inner circle of federal policymaking. But the Vietnam War galvanized opposition among scientists, who increasingly were targets of conservative politicians. Much of the animosity was cultural: Scientists were seen as cosmopolitan intellectuals or European émigrés with liberal politics. Though Nixon did not, in fact, slash funding for scientific research, the scientific community saw itself as beleaguered from multiple directions.

The Charpie Report’s core message was to call out a general “abundance of ignorance” about the nature of innovation.

The Nixon administration sought to clarify its disjointed science policy by elevating innovation as its organizing principle. Ideas and programs long circulating in Commerce began to be taken up by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the White House’s Office of Science and Technology (OST). The administration’s “New Federalism” approach of returning power to the states bore much in common with the Creative Federalism of the Johnson administration. It expanded on the Charpie Report’s image of an entrepreneurial nation thwarted by complex structures and unintended consequences that no one fully understood. New programs were to remove that ignorance through research into the innovation process, investment in incentives, and the elimination of regulatory “barriers” to innovation. The key difference in Nixon’s vision of innovation was a stronger emphasis on the role of markets in social change. Hollomon’s goals of innovation services through land-grant universities remained, but the focus shifted toward the “start-up” problems of new companies and the elimination of regulatory barriers to new innovations.

Two senior bureaucrats guided innovation efforts inside the Nixon administration. The first, Edward E. David, was appointed as presidential science advisor after a career at Bell Laboratories. The second, H. Guyford Stever, became NSF’s director in 1972. Stever, most recently president of Carnegie Mellon University, was a longtime Nixon supporter who fashioned himself as a scientific everyman, more at home hunting and fishing than in the cosmopolitan circles of his academic peers.

The Department of Commerce led the Experimental Technology Incentives Program (ETIP), the first of two parallel innovation initiatives launched by Nixon. Its initial director, Lewis M. Branscomb, was a physicist in the National Bureau of Standards who spoke boldly for enhanced engagement between science and society through evidence-based industrial partnerships, deregulation, and new market creation. ETIP’s mission included programs for helping bureaucrats become change agents; research on the impact of deregulation in the railroad, pesticide, and pharmaceutical industries; and studies of the nature of innovators.

NSF led the second initiative, the Experimental R&D Incentives Program, designed to help bring science to market. Its director, C. B. Smith, was one of the few NSF employees with industry experience. He assembled a group of social scientists to examine the efficacy of public-private partnerships, the impacts of tax incentives, and the value of prizes to stimulate innovation. Still, NSF was cautious about making “political” choices. The agency described Experimental R&D Incentives as a source of nonpartisan, objective advice that could assess empirically how innovation worked. In other words, the initiative was intended to make innovation “scientific” through assessmentand accountability.

Scientists were seen as cosmopolitan intellectuals or European émigrés with liberal politics. Though Nixon did not, in fact, slash funding for scientific research, the scientific community saw itself as beleaguered from multiple directions.

Nixon announced this suite of innovation programs during his 1972 reelection campaign. In the nation’s first Special Message to the Congress on Science and Technology, the president praised science but argued that “the mere act of scientific discovery alone is not enough.” Future prosperity required combining “the genius of invention with the skills of entrepreneurship, management, marketing, and finance.” Instead of continuing to invest in basic science and classified weapons research, Nixon’s plan would target the domestic economy to “bring together the federal government, private enterprise, state and local governments, and our universities and research centers in a coordinated, cooperative effort to serve national interest.” His administration would authorize NSF to work on research applied to national needs, reform patent policies to make federal discoveries available to private firms through licensing, and initiate a series of incentives to enhance the climate for innovation. Finally, the president himself would honor a small group of creative Americans with an award on par with the Nobel Prize.

A Nobel Prize for innovation

The Presidential Prize for Innovation defined what counted as innovation and who was an innovator during a transformational moment in science policy. However, different entities emphasized different values of innovation through the prize. For Nixon’s Domestic Council, the prize would honor social or institutional returns on public investment. For Stever and NSF, the prize was about retaining and reframing their identity as the country’s source of scientific progress. For Branscomb’s new ETIP program at Commerce, the prize would “encourage the best young scientists” to work in applied research. Lastly, for DeSimone, the prize was a culmination of Commerce’s innovation advocacy, offering exemplars of American innovators while also building crosscutting ties across government and industry.

The innovation prize also was an attempt to redefine the image of science. In contrast to the Medal of Science, an honor for lifetime achievement with no financial reward (which Nixon conspicuously failed to award in 1971), the innovation prize would come with a cash award as a “stimulus to creative endeavor.” In this aspect, the prize also reflected Nixon’s disdain for elites. The competition would be open to anyone, rather than only those nominated by scientists.

The prize’s rollout was rushed and disjointed. Nixon publicly announced the prize before deciding how the awards would be funded or what would count as a national innovation. Science and engineering societies received requests for nominations less than two weeks prior to the prize deadline. And the competition was not advertised in national media nor to groups such as the NAACP, whose advocacy might have broadened the pool of potential women and Black innovators.

Despite these problems, and after a short extension, the competition yielded 461 entries that ranged from scientists and engineers to corporations, university departments, garage tinkerers, and Catholic nuns. Innovations included antibiotic drugs, chemical processes, solar heating devices, holography, numerous advances in computing, the Saturn rocket, the Bay Area Rapid Transit System, environmental monitoring systems, packaging plastic, and a program for rehabilitating convicts (led by the nuns).

Amid the collapse of faith in government, exacerbated by Nixon’s downfall, a very different American vision of innovation had just started to take shape along Boston’s Route 128, in Silicon Valley, and on the pages of New York magazines.

In August 1972, the White House selected six winners: Samuel Ruben, an independent inventor in the Edisonian tradition; Harold Rosen, an aerospace pioneer; Willem Kolff, a biomedical engineer; Edward Knipling, an entomologist and environmentalist; John Backus, a computer scientist; and—overturning the advice of the prize’s advisory board—Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett, creators of Sesame Street. None of the intended recipients of the Presidential Prize for Innovation are household names today. Even at the time, they were unfamiliar to most Americans. The prize was designed to rectify this; by elevating their achievements, it promoted a uniquely American social type and showcased the government’s central role in powering innovation.

Bipartisan myths

On September 15, 1972, instead of celebrating the nation’s innovators, the White House received the first indictments in the Watergate scandal that brought down Nixon’s presidency. The prize ceremony was postponed. Then postponed again. With the exception of an inquiry in Science asking “Whatever Are the Presidential Prizes?” the award disappeared with little notice.

Prize missteps signaled disarray in the government’s nascent innovation policy. Just months after initial planning for ETIP, Branscomb left the administration for a job at IBM. In January 1973, David resigned as OST head, lamenting that his ideas were not heeded. Rather than replace him, Nixon abolished the entire office. Stever then assumed a dual role as White House science advisor and NSF director, where he continued to reshape the government as an innovation catalyst. DeSimone, for his part, became an innovation czar under Stever, and earned minor notoriety for attempting to convert the United States to the metric system. In October 1973, a distracted Nixon granted the National Medal of Science after a two-year hiatus with a speech that failed to mention the word innovation. Four months later the president resigned.

The setbacks of the bureaucratic innovators were temporary. Some, such as Hollomon, had short government tenures, but they continued to spread the innovation gospel around the world. Others, like DeSimone and Branscomb, spent their careers serving government across decades of partisan swings. As a result of their efforts, every presidential regime since has made “innovation policy” central to its administration.

Still, the prize fiasco revealed the tenuousness of the myth of innovation and civic harmony. Amid the collapse of faith in government, exacerbated by Nixon’s downfall, a very different American vision of innovation had just started to take shape along Boston’s Route 128, in Silicon Valley, and on the pages of New York magazines. Its heroes—digital disruptors and billionaire entrepreneurs—portrayed start-up culture as the driver of societal change.

Today, as these “unreasonable men” themselves become bureaucratic innovators, it is important to recognize what we have lost. Nixon’s prize presented innovators as civic heroes—entrepreneurial but not necessarily entrepreneurs, working within government or in partnership with it, on innovations that were infrastructural or based on federal investment. They represented a society in which individuals, corporations, and government agencies all had a part in making a better world.