Creating a Popular Foundation for the Bio-Age

A nationwide network of public bio labs is needed to enable a truly participatory bioeconomy.

In 2020, Stanford University abruptly shut down laboratory operations due to the pandemic. A team of undergraduates competing in iGEM, the global bioengineering competition, were left in a quandary. How could they develop their novel COVID-19 diagnostics for this competition without a proper lab? Luckily, they heard about BioCurious, a community biology lab in Santa Clara, California, that was operating with pandemic precautions. Not only did it have the equipment to enable meaningful progress on the team’s project, it also had mentors. The students ended up winning a gold medal at the competition. More importantly, they felt empowered as leaders in scientific research moving forward.

In hindsight, the team came to see the closing of Stanford’s labs as a silver lining. At BioCurious, they had the opportunity to learn in a different environment than an academic campus alongside a diverse group of scientists and entrepreneurs who enthusiastically supported them. BioCurious, which has been sponsoring community iGEM teams since 2014, was designed to foster exactly this kind of community in a supportive environment that teaches and reinforces responsible biosafety practices.

Today, the United States stands to bring the innovations of emerging biotechnologies to scale, growing a bioeconomy that will transform agriculture, medicine, domestic manufacturing, energy, and defense. However, this ambitious vision cannot be actualized if activity is limited to Boston, San Francisco, San Diego, Seattle, and a few biotechnology hubs. To ensure everyone can participate in and gain the most from a booming bioeconomy, many more communities must have access to biotechnology at the local level. We believe that a national network of thousands of local labs, like BioCurious, could enable all Americans to responsibly discover and innovate with biology.

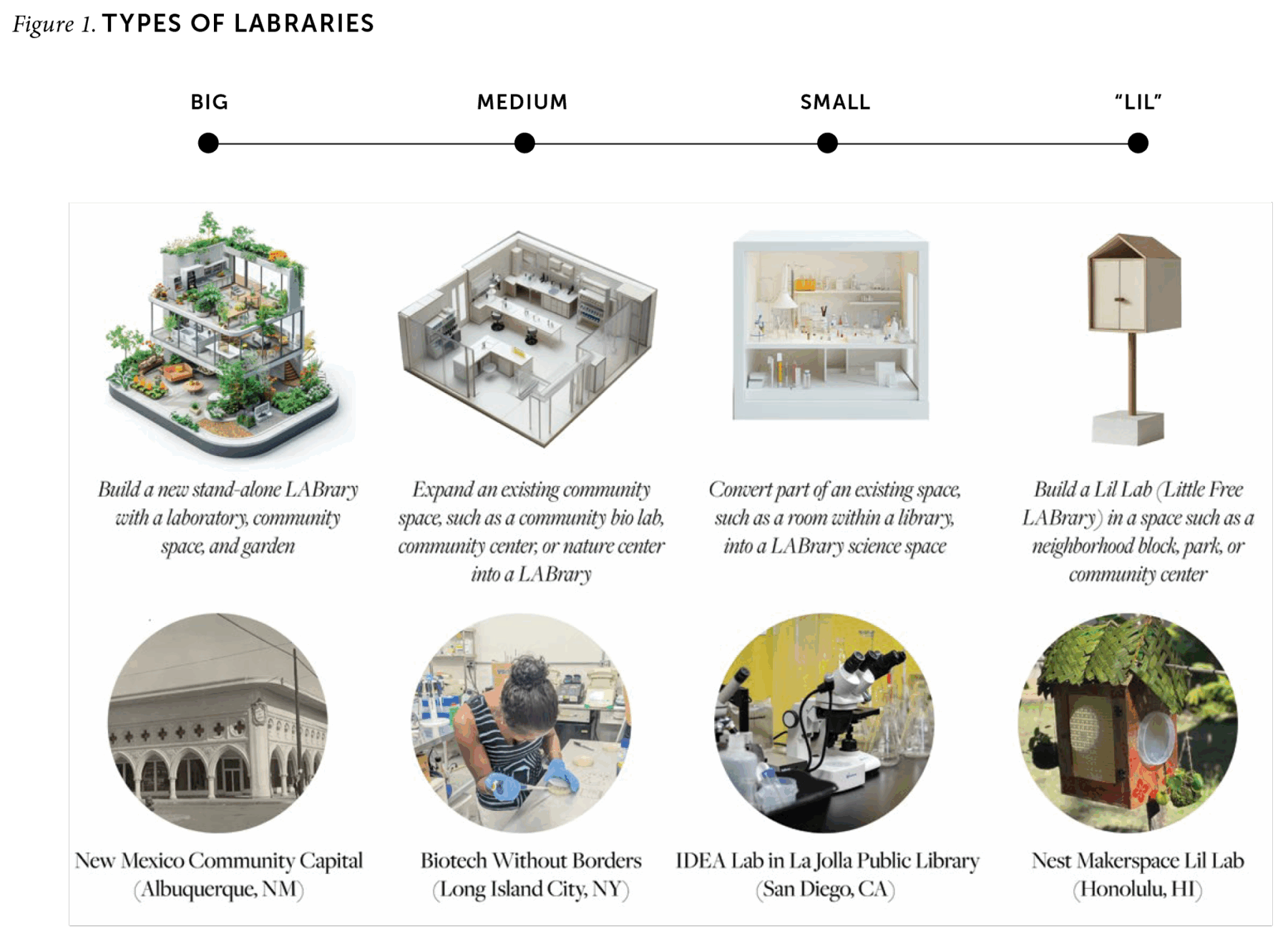

Much as local libraries laid a foundation for the information age by building American literacy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, community bio labs—we call them LABraries—could usher in the bio-age by building bioliteracy. We envision LABraries as essential civic infrastructure to support scientific research, the prototyping of innovative and entrepreneurial ideas, and workforce training in different community contexts. By mobilizing community resources, including equipment, expertise, and connections to local businesses, LABraries could help people solve problems at multiple scales. A national network of LABraries could also nurture a generation of people—LABrarians—skilled in helping others discover and use biotechnology safely and responsibly. In such a fully participatory bioeconomy, every community would be in a position to actively shape the future of biotechnology and harvest its benefits.

Much as local libraries laid a foundation for the information age by building American literacy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, community bio labs—we call them LABraries—could usher in the bio-age by building bioliteracy.

LABraries as public infrastructure could play an important role in shaping the trajectory of the bioeconomy, multiplying its beneficiaries and extending its capabilities. US domestic biomanufacturing will require investment at regional and local scales; addressing local needs through LABraries could create a “mom-and-pop” bioeconomy. Something analogous has already occurred with microbreweries, which use equipment similar to what’s needed at small and medium fermentation facilities. Local manufacturing infrastructure along with LABraries could be leveraged in times of crisis to supplant international supply chains and produce critical materials locally.

Empowering a broadly bioliterate citizenry will hasten the transition to a whole-of-nation bioeconomy. Today, regions that do have biotechnology training programs are rarely located in areas with greater bioeconomic potential, such as the American Midwest and South. Enabling every community to contribute, bringing their unique cultures, expertise, and interests to bear, is necessary to grow a scalable and trustworthy bioeconomy. LABraries could serve as the “last mile” for biomanufacturing, training and enabling the next generation of workers, researchers, and entrepreneurs to define the future of the bioeconomy.

Labs + libraries = playbook

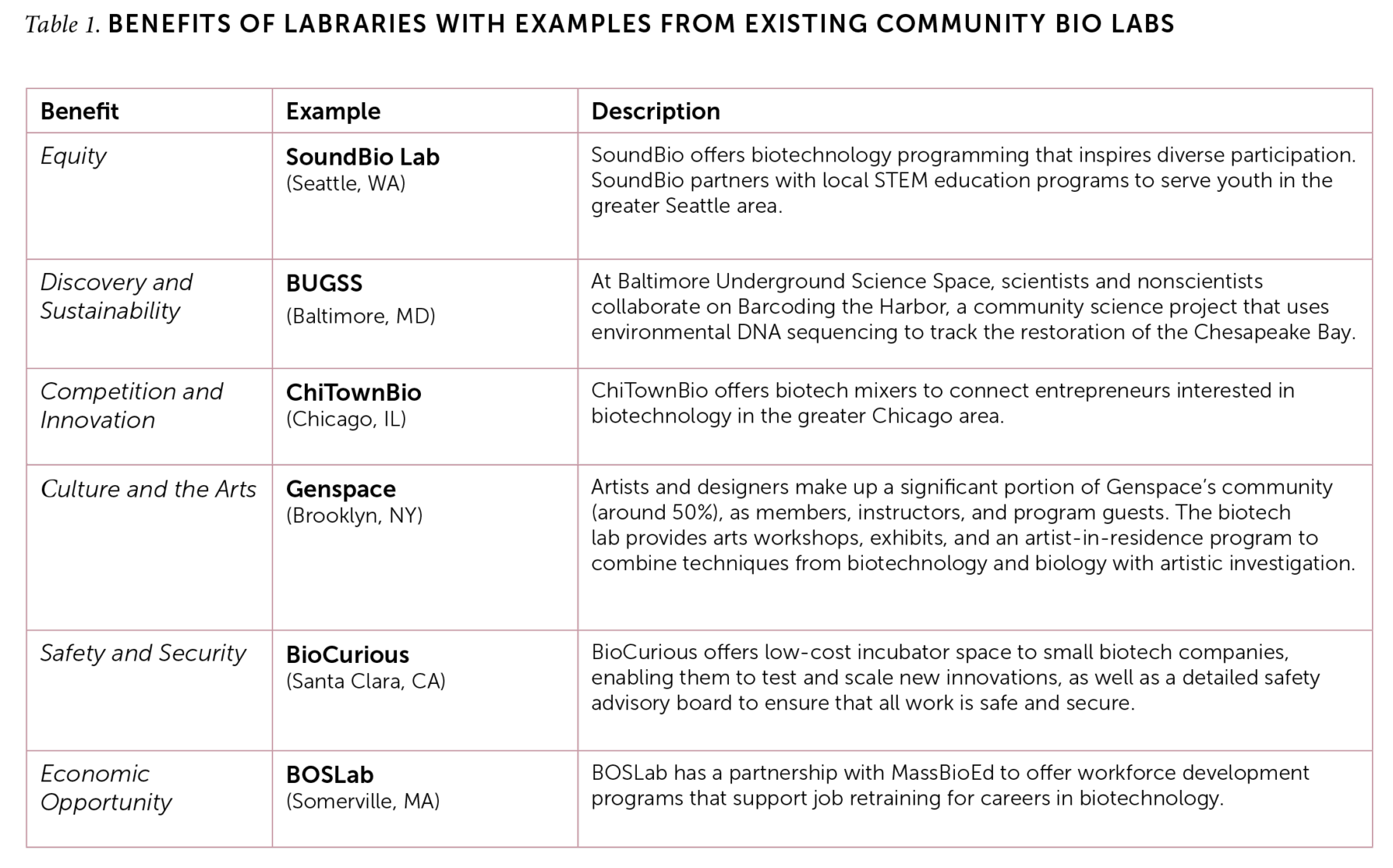

Some of this community laboratory infrastructure already exists in the United States, but its impact has been limited by funding and geographic distribution. Today, community bio labs can be found in New York City, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Seattle, Oakland, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and a few other locations. They have facilitated ongoing research projects, such as DNA-based environmental monitoring of habitat restoration in the Chesapeake Bay and sequencing the first angelfish genome. They have also played an important role in education, hosting science competition teams like iGEM, hands-on molecular biology tutorials, art workshops using biomaterials such as fungus, youth science outreach programs, and more (see Table 1).

However, most community bio labs operate on a limited budget, with limited or no paid staff, and are supported primarily by workshops and low-cost memberships. Few grants or structured funding mechanisms exist to support community bio labs, and lack of funding has been cited as a significant cause of bio lab closures. To catalyze the transformative potential of community bio labs, we need to increase their numbers greatly, support their staff, and help them spread across the nation.

Doing so would not be the first time the United States has transformed its educational and cultural landscape using a library model. In the early 1890s, industrialist Andrew Carnegie donated about $40 million (about $1.3 billion today) for the construction of 1,679 physical library buildings in 1,412 towns across the United States. The foundation of Carnegie libraries rested on a simple agreement: Carnegie provided the physical infrastructure for the library while community members would “provide books and maintenance for the donated building,” as a history of the libraries attested. It was important to Carnegie that the libraries were not a passive gift, but a “democratizing institution.… [where] all were free and equal.” The libraries were intended to provide the means for people to actively direct their own edification.

Carnegie’s investments in infrastructure were accompanied by investments in expertise. In 1887, librarian Melvil Dewey (of Dewey decimal system fame) began a school of “library economy.” The field grew rapidly in the early 1900s as Carnegie himself encouraged professionalization of librarians, endowed a library school, and funded the profession.

LABraries could be similarly leveraged to support LABrarians as professional community scientists. LABrarians would oversee the activities within the LABrary, ensuring that practices are safe, ethical, and secure. But they would also serve as networkers, connecting community members and educational institutions, nonprofits, and businesses through workshops and other programming. With other LABrarians, they could build and maintain open-source databases; collaborate with local researchers and organizations to offer classes and programs; and deploy the latest research in their community context. We envision LABrarians as a new profession, where individuals could pursue a certification from colleges, universities, and other accredited institutions.

LABraries could support the development of an educated biotech workforce by offering self-study, job training, microcredentials, and internships.

Like Carnegie’s libraries, LABraries could support the development of an educated biotech workforce by offering self-study, job training, microcredentials, and internships. As trusted and easily accessible places for people to re-skill into new domains and connect with local employers, LABraries can join libraries as foundational pillars of resilient local economies.

The models are close enough that LABraries could be co-located at many existing libraries or similar community spaces, including gardens or nature centers. Already, many libraries offer makerspaces or other infrastructure beyond books, which could be expanded by adding basic scientific equipment and expertise. Biodesign educator and LABraries project advisor Corinne Okada Takara, who was active in the early makerspace movement, explains that libraries are viewed as particularly welcoming because they offer “consistent educators and spaces that nurture multigenerational, sustained exploration.” She believes that biodesign programming can build on that foundation, “extending into library makerspaces as a natural, community-rooted evolution in these trusted, inclusive settings.”

Transforming American society so that more people can make use of biotechnology will require a nationwide approach that engages public and private partnerships and leverages both physical and human capital at the local level. Inspired by the Carnegie model, national funders could enable LABraries to grow at scale through public-private partnerships while empowering the people who staff them to network and build expertise. Community entities would then be positioned to guide the design, programming, personnel, and upkeep of each LABrary—so that each one supports the kind of economic and cultural development that their community desires and values.

Why biotechnology requires a proactive approach

Earlier emerging technologies, such as electronics, programming, and robotics, have diffused into society through traditional channels of higher education and their availability in the market, supported by clubs and contests for students. But biotechnology is different—it needs specialized facilities and training in safety. To become part of the everyday life of citizens and consumers, biotechnology requires a proactive, deliberate approach.

In part, what makes biotechnology different from previous emerging technologies is its deep cultural roots: The process of working with biology is rich with meaning and emotion, whether using ancient Peruvian terraces for experimental potato farming or tinkering with beer or pickles. Another aspect that makes biotechnology different is that it is us—humans and all other living creatures are biological—giving rise to responsibilities as well as fears.

Biotechnology is, of course, powerful, and a variety of fears reflect that. As with genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, there is significant cultural worry that biotechnology leads to unnatural life forms or that its practice has innately dangerous consequences. Some of these fears can influence communities’ attitudes towards biotechnology products and facilities. As the field grows, some risks—such as the potential for negative effects on local communities—will also increase, requiring that communities learn how to engage constructively with them. LABraries can provide accessible yet supervised spaces for the public to learn about and safely engage with biotechnology, building trust by sharing concerns and empowering communities to benefit more directly from locally relevant biotechnologies.

To proactively safeguard against future risk, any publicly accessible community lab space must have robust biosafety infrastructure, complete with specialized equipment, practices, and norms, and high degrees of expertise. Oversight of LABraries would be the responsibility of trained and certified LABrarians. By making biosafety education a regular part of daily life, rather than delaying it to college-level courses, LABraries can empower Americans of all ages to contribute to biosafety and biosecurity.

This approach builds on earlier models of community outreach, such as the Cooperative Extension Service and 4-H, which empower citizens to use new scientific knowledge to improve agriculture, nutrition, and family incomes. During World War II, 4-H members organized efforts such as Victory Gardens to grow enough food to sustain themselves, leaving more commercial products to be sent to troops.

The process of working with biology is rich with meaning and emotion, whether using ancient Peruvian terraces for experimental potato farming or tinkering with beer or pickles.

Following a similar template, LABraries can be used to equip the public to respond to a variety of national security threats. For example, when global supply chains were disrupted during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, LABraries could have served as hubs for local manufacturing and community resilience. Just as makerspaces and community groups mobilized to provide masks and 3D-printed face shields to essential workers, so a national LABrary system could be repurposed for domestic manufacturing and education in the case of a biological threat. Decentralized models to produce strategic materials and medicines may be necessary in times of catastrophe or conflict. Meeting these future threats requires developing the “people power” now.

LABraries present a distinct vision and model: Science that is of the people, by the people, and for the people. Where previously self-taught enthusiasts might have tinkered at home alone, the LABrary can be a safe and stewarded environment where budding entrepreneurs, innovators, scientists, artists, and everyone else can receive support and guidance to pursue work responsibly. LABraries could also expand the network of people involved in science by welcoming researchers to work directly with the public to set research agendas and support participation in original research projects. Because biotechnology requires trust between practitioners, experts, engineers, and the public, it can also cultivate sustained collaborative relationships among diverse stakeholders. Thus, LABraries could be a launching pad for a culture of bioinnovation, as well as the birthplace of renewed public confidence in science. In this way, LABraries could become part of a civic science infrastructure that empowers the use of knowledge for a better life for everyone.

Transforming American society so that more people can make use of biotechnology will require a national approach that engages public and private partnerships and leverages both physical and human capital. Combining the historical precedent of Carnegie libraries with the experiences of existing community bio labs offers a playbook for developing a network of LABraries across the United States. By enabling as many different LABraries as there are communities, a national LABrary system could create expertise and trust at the grassroots level while fostering a thriving bioeconomy at the national level.