What Does a Cormorant Feel?

People know that their pets are unique individuals. Each dog has his or her own quirks, likes, and dislikes. But what about cormorants? Research reveals that wild animals are just as uniquely individual as our pets. Rats show empathy. Crows can hold grudges. Even termites have different personalities. What would it mean if society took animal intelligence and self-awareness seriously?

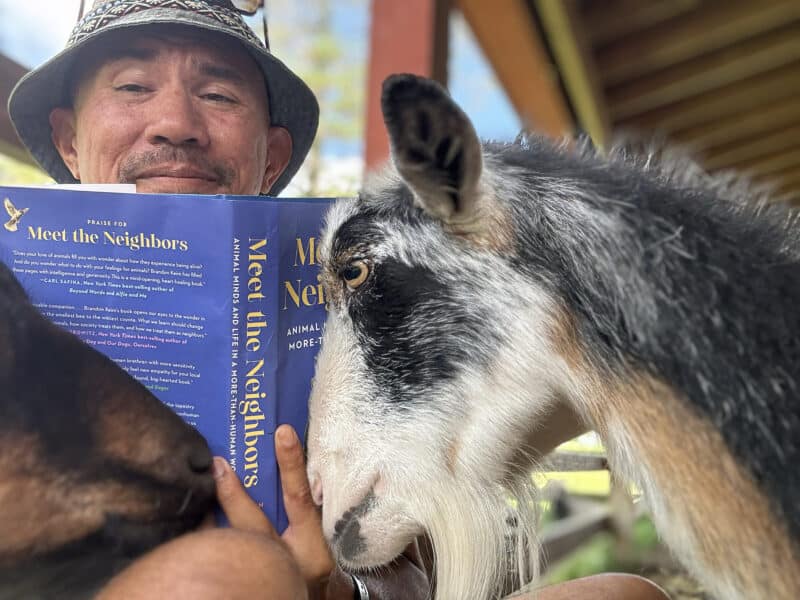

Lisa Margonelli explores this question with Brandon Keim, author of the recent book Meet the Neighbors: Animal Minds and Life in a More-than-Human World. Keim also wrote about animal intelligence and what it might mean for policy for Issues in the Spring 2025 issue. In this episode, Keim discusses animal personhood, movements around animal representation, and cormorants—one named Cosmos in particular.

This is our last episode before our summer break, but we will be back in September with a miniseries about rethinking disasters. Write to us at podcast@issues.org with your thoughts on this season and other ideas you’d like us to explore. Subscribe to the podcast and our newsletter to be the first to hear when we return.

Resources

- Learn more about animal individuality by reading Brandon Keim’s book, Meet the Neighbors: Animal Minds and Life in a More-than-Human World.

- Keim explores the policy impacts of new research on animal intelligence in his Issues piece, “When That Chickadee Is No Longer ‘A Machine With Feathers.’”

- Visit Keim’s website to find more of his work.

Transcript

Lisa Margonelli: Welcome to The Ongoing Transformation, a podcast from Issues in Science and Technology. Issues is a quarterly journal published by the National Academy of Sciences and Arizona State University.

If you’ve ever spent time with a dog, you know that every one is an individual. They all have their own quirks, likes, dislikes, hopes, dreams, and concerns. But wild animals are just as uniquely individual as our pets. Rats show empathy. Crows can hold grudges. Even termites have individual personalities. What would it mean if society took animal intelligence and self-awareness seriously?

I’m Lisa Margonelli, editor-in-chief of Issues, and this is our last episode before we break for the summer. I’m really excited to be joined today by Brandon Keim, who is the author of a recent book that explores animal intelligence. It’s called Meet the Neighbors: Animal Minds and Life in a More-than-Human World. Brandon also wrote a piece for Issues about how policy for wild animals could change based on recent research.

Brandon, welcome. Thank you for joining us.

Brandon Keim: Thanks for having me.

Margonelli: I’m very happy to get to talk to you. At Issues, we spend a lot of time talking about policy that’ll make science better. And what’s really interesting is that your book, Meet the Neighbors, is really about how science can actually make policy better, or more appropriate, or just more in tune with what the world is.

And your work is really about, I think, what is one of the most profound cultural and spiritual transformations of our time, which is how science is changing our understanding of animals, and by extension, ourselves and our politics. I wanted to start off by just asking you, what kind of science were you looking at in Meet the Neighbors?

Keim: I’ve actually come, in the course of writing Meet the Neighbors, and the time since I originally filed that manuscript, I’ve kind of come to think less of science as changing the way that we think about animals, or really revealing, fundamentally surprising things about animals, but rather that science is reaffirming a lot of things that people already suspect, or people already know in their own experience, and just kind of, if you’ll forgive the phrasing, giving permission to people to think about other animals as intelligent, thinking, feeling beings, and not just certain animals here and there, not just, oh, chimpanzees, and parrots, and dogs, of course, and maybe cats, but not all those other animals, but really, to think about other animals consistently that way.

And that being said, I don’t want to also make it sound like science is just rediscovering all these things that we already know, because that’s not the case. And of course, new things are being learned all the time. But just fundamentally, I think a great many people think, and have thought for a very long time, of other animals as being fellow persons. And in a very general sense, science is just supporting that now.

So with that said, the question of what science I drew on, a great big fruit cake of it, a nice dense fruit cake of science, just researchers who were doing observational work, experimental work, studying everything from the very basics of cognition, to more complex social relationships, and behaviors, and communication, and so on. And I drew on a lot of philosophy too, a lot of the humanities.

These last 15 or 20 years, there’s kind of been what people there sometimes call the animal turn, which is just, basically, all of these scholars turning their attentions to animals, anthropologists, and sociologists, and theorists, and everybody just thinking about animals in really new, more rigorous ways. So I bring in a lot of that as well too.

Margonelli: You spent a lot of years on this book. How long did you spend?

Keim: Oh, my God, a long time. Well, it’s sort of…. Let’s just say, the original genesis of it, back in 2015 or so, I thought it was just going to be like a straightforward animal intelligence book. Like a, “Here’s new amazing things about the minds of animals.”

And I was fortunate that I had some agents and publishers tell me, “Oh, there’s many of those books out there. There’s no room for any more.” Which was totally wrong, there have been so many of those books since then, and they’ve all done so well because people love that stuff.

But the good part of being given that somewhat not good advice is that it really forced me to think about, okay, what do I want to do in my book that’s different? And so a question that I try to answer, really, Meet the Neighbors, it has four sections, and the first section is the distilled version of that original animal intelligence book that I wanted to write, where I’m taking the science and putting it onto a landscape, in this case, the landscape of a suburban eastern North American neighborhood, and really trying to map the findings onto the animals you’re likely to meet there.

And which for me, one of my frustrations with the format of science journalism, and in the way that books about animal intelligence often read, is that they almost make the animals feel abstracted to me, and they make the findings feel distant, something that exists in a lab, or on the pages of a scientific journal. But you don’t really feel them in your heart when you just go outside and see a robin.

Margonelli: Well, you also see them as a specimen, rather than as your neighbor, or your co-liver, a part of your life whom you are interwoven with.

Keim: Absolutely. You see them as a specimen, like an emblem of their species, not a fellow individual. And so the first section of the book really is about that science. But then the rest of the book is just asking the question, okay, what do we do with this appreciation of animals? And just kind of like, okay, is it just, “Oh, gee whiz, here’s some great facts”? Or do we also say, “Okay, if we understand animals this way, if we empathize with them, what do we do with that knowledge? Where do we go with that understanding?”

Margonelli: So this idea of really wanting to see the animals as individuals is, I think, really interesting. And for me it came up in the section about cormorants. So there’s a lot of really interesting stuff in the book. And I’m just going to pick one chapter, because it has a really interesting depth. And it also has cormorants, and I grew up in Maine, I still live in Maine. Cormorants have a funny reputation.

I mean, they’re kind of oily. They’re very dark-colored, so they’re not a pretty bird, like a mallard that has green on it. They have a lot of distinctive behavior, like they hang around with their wings out akimbo, and they’re just like their armpits a lot. And so they’re very distinctive. They’re easy to see. They have this kind of long bill.

But they’re really seen as a dirty bird or a super predator. People accuse them of eating all the fish. I have an uncle who was accusing them of eating all the fish in Casco Bay, which is really a large bay. And so they just have this bad bird reputation. And I just want you to talk a little bit about the bad bird reputation.

Keim: So I too grew up in Maine. This is a whole Maine represent podcast. And I too grew up thinking of them as bad birds. And they were the bird, it was okay to throw rocks at them, because… I mean, I never hit a cormorant with a rock, I should just say. But yeah, they were the birds who ate all the fish, and they were bad for centuries. Really, for millennia, cormorants have been vilified for eating fish.

And part of what’s unique about their vilification, so lots of animals get vilified for competing with humans. There’s many other fish eating birds who are not vilified to the extent cormorants have been. And I think part of that really just does come back to their appearances. They’re black, and oily, and they’re in the Bible as a devilish bird, and all of it.

And so in the United States, we always hear about passenger pigeons, is this example of just the wholesale slaughter of animals in North America. But, oh my goodness, people went to town on cormorants too, and just annihilated them across continental North America. And not just annihilated them, but really did it in some spectacularly cruel and mean ways. And thankfully, that came to an end in the early 20th century, because of conservation legislation. And they had at least some respite then. And then with the advent of DDT and other environmental chemicals in the middle of the 20th century, then they just got hit right back yet again.

Margonelli: It’s really interesting, because after the DDT really knocked them back, then they finally started coming back. And I think recently, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has enabled people to do culls of more than a hundred thousand birds a year. So the thing is that this myth about cormorants being a bad bird, connects to the way they are both protected and targeted by conservation policy.

Keim: And these culls, it should be said, the culling is not a new thing. The culling has been going on for decades. And the two big flashpoints have been their predation on aquaculture in the eastern and southeastern United States. But really, the most high-profile examples involve their predation on salmon in rivers in the Pacific Northwest.

And it should be said, there have been conservationists, and I think especially some of the Audubon groups, who have been really fighting hard to protect cormorants, and just saying that they’ve been the easy scapegoats. The big problems of salmon in the United States, and especially in the Pacific Northwest, it’s not cormorants, it’s dam building, and overfishing, and the fact that they’re only able to spawn in a fraction of the waters they once would have spawned in. And then the ones who do spawn are then getting hit by commercial fishing pressure as well.

But those are difficult problems to solve. Whereas, killing cormorants is easy. And also, killing seals and some other aquatic mammals as well, that happens too. So they just get scapegoated. But now in recent years, the scale of the culling has been allowed to expand dramatically, both in Canada and in the United States. And in both cases, the policy procedures by which the culling has been expanded has been really problematic. But in Canada, it’s just been awful. At least in the United States, it’s sort of like, there’s a plausible procedure. I think nobody involved in it spoke for cormorants, which is really a key theme of that chapter, the idea that animals should have representation.

Margonelli: Cormorants, they’re the scapebird, they’re the bad bird, there’s a myth attached to them. But you actually wanted to know more about cormorants, and maybe cormorants as individuals. And so you ended up talking to an ecologist named James Ludwig. Tell me about his experience of the individuality of cormorants.

Keim: So one of the things that I tried to do in the book is to have an animal character in every chapter. And it’s really a convention. If I was writing about issues involving only human beings, then of course there would be human characters all over the place. But in writing about nature and about conservation, it’s still pretty rare for there to be true animal characters who are rendered with a biography that is as rich and real as what we’d write about a fellow human person.

So in the cormorant chapter, I just happened across a story of a biologist named James Ludwig, who worked on the Great Lakes. And I found these photographs of him with a cormorant, whom he named Cosmos, who had just this terribly deformed bill, just corkscrewed and scissored around. And the reason the cormorant’s bill was like that was because the cormorant had been affected by heavy metal pollution.

And Ludwig, his job was to document the effects of heavy metal pollution on shore birds in the Great Lakes. This is back in the early 1980s. So he would just go from nest to nest, and if he found a bird who just clearly could not survive, then it was his job to euthanize that bird. And so, one day, he’s just been killing bird after bird, and his heart is so heavy. And he finds this poor, deformed cormorant, and he knows that he’s supposed to kill her. And he’s just like, I don’t want to do that. I am going to take this bird home and try to take care of her.

And so he did that. And he named the cormorant Cosmos. Sometimes people use the word imprinted, which I think almost cheapens the relationships that formed. He cared for Cosmos, and Cosmos cared for him.

And so he raised Cosmos, and Cosmos would swim in his pool, and hop up on his lap, and turn the pages of science journals as he was reading. And then when he would drive to state houses, and legislatures, and go to give talks all across the upper Midwest, he would travel with Cosmos. Cosmos would sit there in the car with him, head on his shoulder just like a dog. And then, of course, Cosmos also made a really great presentation partner when it came time just to really put a face on how terrible these chemicals were.

That was Cosmos. And it was just such a unique story. I’ve never heard another story like that of a human person and a cormorant being so close.

Margonelli: And the cormorant would groom him.

Keim: Mm-hmm.

Margonelli: Cosmos would groom his sideburns, because it was the ’80s. And they had this very, it wasn’t a one-way relationship, it was a two-way relationship. Cosmos seemed to know when he was anxious.

Keim: Mm-hmm. And there was this one lovely story he had where I think he had given a presentation, he was trying to get a grant or something like that, and he had been rejected. And so he’s making the long drive home, and he’s just despondent. And Cosmos just seems to pick up on the fact that he’s feeling bad, and starts to groom his sideburns, and try to comfort him. And it was just really a beautiful story.

Margonelli: It’s a beautiful section of the book. And I cried the first time I read it, and I cried this time when I looked at it this afternoon, before talking to you months later. And I think that’s an interesting thing. That’s weird in itself, and I’m going to come back to that empathy.

But for right now, I want to go on to one of the things that’s happening now is that there are groups of philosophers who are making the argument that our relationship to animals is not just moral, it’s deeper than that, that they are part of society. They are part of us, and they need to have political representation, in a world that is, as people at Issues like to say, very techno-social, this combination of technology and society where politics is extremely important.

Let me just read you a quote from your book, from the Dutch philosopher Eva Meijer, who wrote a thesis called When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy. And she said, “Other animals have languages and express themselves in many ways, but they cannot make themselves heard in the dominant political discourse, because they do not speak the language of power. And in light of this, they should not be seen only as intelligent, but also recognized as a political group.”

Keim: Yeah, so Meijer’s work is fabulous. And there have been this group of philosophers and theorists who have really taken the step from just thinking about animal rights, to also thinking about what it means for animals to have representation. What Meijer is really filling in is, in the western liberal democratic tradition, we put so much emphasis on language, and on speech, and on communication. And we put that emphasis on communication, both as a grounds for moral recognition in the first place. If you have language, then you’re somebody.

And so what Meijer is filling in is saying, “Well, wait a second, if language and communication is so important to us, well, animals communicate and have languages of a sort too. And there’s some fine-grain distinctions to be made there. And I would actually argue philosophically that really, that only humans have language. But I also think that language is just a subset of meaningful communication. And meaningful communication is what matters. And that is all over the place. Animals do that.

Margonelli: What I find really interesting about this philosophical work is that it has led to direct political outcomes. Canada has an Animal Protection Party and the Netherlands has the Dutch Party for the Animals. So you have these people starting to align themselves with the political rights of animals, which is sort of one way to solve the issue of the animals not having language. And there are many other ways to address that issue, if that is your primary issue. But what’s really interesting in there is that the Animal Protection Party actually figured out a new policy plan for cormorants.

Keim: Yeah, so I wouldn’t quite say that it’s not like the politics has followed from the philosophy, but rather that the political examples I highlight, I think, are real world examples of these philosophical ideas just being lived out, not by people who have this high level philosophical abstract understanding of it, but just people doing the right thing. And this is what it looks like.

And I think, could then be done in a much richer way. But so for what’s going on in Toronto, Toronto is the site of the largest cormorant community in North America. It’s extraordinary. It’s roughly, I think it’s about, I’m going to say 30,000 nesting pairs. And I might be off a bit there, but it’s a heck of a lot, and just a glorious sight. They’ve built their city, as it were, on this little spit of abandoned land right there on Lake Ontario.

And then there’s been a lot of fighting over what needs to be done about them, because for some people, and this is coming back to the way that cormorants are vilified, the idea that their droppings are killing vegetation on a few acres is somehow considered this terrible thing that needs to be fixed, even though, of course, that’s only a tiny fraction of all the trees that are cut down in the greater Toronto area every year.

And then also that idea of, oh, they’re smelly, they poop on people’s boats, they’re eating all the fish, and all of that stuff. So there’s a lot of people who have wanted to just to kill all those birds. And then there’s other people, and Liz White from the Animal Protection Party in Canada, and just other animal advocates, really, and this didn’t come as much from the conservation community, just fought back and said, “No, don’t kill these birds. We don’t want you to do that.” Put up a fight.

And what they eventually arrived at was a committee of people who came together to figure out what to do about the cormorants. But what was special about this is, on that committee, there were people who were speaking explicitly for the cormorants, which is something that really does not happen very often, if ever, in conservation decision making. Not just people from environmental groups, but people who are advocating on the bird’s behalf.

And they arrived at a really sensible compromise, where their one section of the area has been demarcated for the cormorants, and they are encouraged to nest there, using non-lethal methods. And that’s the solution, encouraging the cormorants to nest in a different place. They don’t get killed. Everybody is more or less happy. And really, right now with the laws that have been passed in Ontario, to allow for basically people to kill as many cormorants as they want for much of the year, that’s really become a unique place and kind of a sanctuary for them.

Margonelli: Interesting. So does the idea of the political parties for animals, maybe it’s where I’m at this particular month in the United States in 2025, but it seemed to be rather hopeful?

Keim: Yeah, hopeful. Hopeful is one word for it. I would say, first of all, you don’t need to have a political party for the animals in order to get that cormorant outcome. It just so happens that some people involved with that party were also involved with the cormorants. The idea of having political parties explicitly for the animals are their own thing. And really, that’s something that you can have if you live in a healthy democracy, with many political parties, which is not the case in the United States.

And so I think it doesn’t map as well onto things here, but outside of political parties, there’s all sorts of other ways animals can be represented in decision-making, such as committees like the one that I mentioned there. Or maybe you can have positions in government, or positions in institutions, like boards of directors. Wouldn’t it be incredible if big institutions had on their board of directors, somebody who spoke for animals?

Margonelli: So as sort of an animal ombudsman.

Keim: Right. I can appreciate how, at this particular moment, this can all just sound so far-fetched. But I think it’s just worth thinking through and using our imagination. And even if there’s not going to be political parties for the animals here anytime soon, you can still just think about what these principles might look like more realistically in other contexts.

Margonelli: I want to return just briefly to my feelings of empathy for Cosmos, the cormorant, because empathy has been the third rail in animal science.

You mentioned that even, to go back to some of what you said at the very beginning, people knew that animals had complex emotional lives. People had hung out with animals, they had a strong sense. But an ideology came into science, which was that you should not be using that empathy. If anything, you should disregard the connections that you saw between yourself as a human. Now, part of this was an attempt to disregard making fables about animals, which is one thing, but part of it was this controversy called the nature fakers. And it just struck me that the controversy over that, and the insertion of ideology into the way we do science, maybe it has some lessons for us. Tell us about the Nature Fakers and if you see any kind of lesson.

Keim: I’m going to give a long-winded answer to this. I think it’s worth zooming out and looking at a longer historical timeline, and really for the last few thousand years. So one of the things that as a young science journalist, I had just assumed that the arrow of progress moves forward and upwards in a steady way. Once upon a time we thought animals were unintelligent, and now look, thanks to science, we’re learning that they are, with this very simple, straightforward story.

And something I came to appreciate more over time was just that for the last couple thousand years, these arguments over whether animals are intelligent in rich ways or not, and whether we, because of their intelligence, have moral obligations to at least consider their interests or we don’t, are just gone back and forth like a pendulum swinging. And so, one strong swing of that pendulum towards recognizing the intelligence of animals, and thinking more ethically about them, was really taking place in the second half of the 19th and the early 20th century.

And of course, one of the most emblematic figures of that was Charles Darwin himself. And what is really so extraordinary about understanding evolution is not only that it puts human anatomy on a spectrum with the rest of the animal world, but also, that it puts our minds on a spectrum with the rest of the animal world, our brains.

And so there, if we’re going to situate this in the late 19th century, early 20th, there’s all this, more and more serious-minded people are recognizing the intelligence of animals. And then there’s a backlash to this. And part of this backlash, as you were mentioning a moment ago, is there was some bad science, some sloppy science being done. Although one of the scholars I talked to for the book actually argues that it’s not like those scientists were being sloppier than scientists anywhere else, and actually, the scientific enterprise would have self-corrected perfectly well.

But there was this rise of belief in the supernatural and in the occult that was really scary and crazy. And this was something that was actually very powerful in the fascist movements in Europe in the early 20th century. And so very understandably, scientists were pushing back against that sort of supernatural, woo-y thinking, and animals got caught up in that.

And then, also, at the same time, out on the landscape rather than in the academy, there was lots more people were thinking about wild animals, looking at them not just as resources, but as fellow kin. And there was all these bestselling naturalists who were writing books. And William Long was the most prominent of these. He wrote, I think, The School of the Woods. And he’s describing animals with rich social relationships, teaching each other, learning from one another, also telling some tall tales and being a bit of a fabulist. So he, and other people, other writers in that vein, end up in this beef with more serious-minded naturalists, including President Theodore Roosevelt himself, who waded into the middle of this. And even, I think he was the one who coined the phrase that they were the, “Yellow journalists of the woods.” And he called them Nature Fakers.

And so that’s hence the name Nature Faker Controversy. And it was basically a fight about how animals and animal intelligence would be depicted in the nature writing of the early 20th century. And ultimately, there was a very rich conversation to be had there. In an ideal world, the discourse would have settled somewhere in the middle. But the Roosevelt side of things prevailed. And that tradition of thinking about and writing about wild animals as fellow persons just became something that happened in children’s stories, but it wasn’t really part of how serious-minded people thought about nature in formal settings.

And that really set, I think, the trajectory of wildlife management, and kind of the way that North Americans have been formally socialized to relate to nature for the last century. And I think we’re having another moment now, where a lot of those tensions are being repeated. And we’re seeing, again, a rise of people thinking about animals in a different way, and also, some pushback against that. And I think we have all of these systems and industries that are really predicated on treating animals a certain way, and thinking about animals a certain way, and they’re just really hard to dislodge. And they end up exerting the sort of gravity on the intellectual world as well.

Margonelli: Thank you, Brandon. It’s been great, amazing to have you here.

Keim: Oh, it’s been such a pleasure. Thank you for having me here. Thank you for reading Meet the Neighbors so closely and making Cosmos a part of our conversation.

Margonelli: Read Brandon Keim’s book, Meet the Neighbors: Animal Minds and Life in a More-than-Human World. To learn more about wild animals and our changing relationship with them, find links to this and more of Brandon’s work, including his piece for Issues, in our show notes. Many thanks to our podcast producer Kimberly Quach and our audio engineer Shannon Lynch. I’m Lisa Margonelli, editor-in-chief at Issues. This is our last episode of the summer, but we will be back in September with an exciting new mini-series about disasters, with host Malka Older. Write to us at podcast@issues.org with ideas for other topics you’d like us to explore.